Mobile Game AB Testing

We’ve talked about AB testing in an earlier post, now is the time to give a full-spectrum run through a real dataset courtesy

of DataCamp.

The fine folks at DataCamp released a project for AB testers to play with focused around data from a game called Cookie Cats. I highly recommend any data-curious people, from novice to experienced, to give their service a shot.

Today’s project is centered around AB testing in mobile games development, we’re going to model the base DataCamp work flow while adding our own twists and approaches as we proceed.

Let’s begin by importing our libraries and data, and seeing what we have to work with!

IMPORT LIBRARIES

# Importing pandas

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Now the data…

READ DATA

# Reading in the data

df = pd.read_csv("datasets/cookie_cats.csv")

Great! So, let’s start our investigation.

EDA

# Check Head

#print(df.head())

# Integrity Check

#df.info()

# Describe

#df.describe()

# Check levels

df.version.unique()

EDA OUTPUT:

userid version sum_gamerounds retention_1 retention_7

0 116 gate_30 3 False False

1 337 gate_30 38 True False

2 377 gate_40 165 True False

3 483 gate_40 1 False False

4 488 gate_40 179 True True

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 90189 entries, 0 to 90188

Data columns (total 5 columns):

userid 90189 non-null int64

version 90189 non-null object

sum_gamerounds 90189 non-null int64

retention_1 90189 non-null bool

retention_7 90189 non-null bool

dtypes: bool(2), int64(2), object(1)

memory usage: 2.2+ MB

userid sum_gamerounds

count 9.018900e+04 90189.000000

mean 4.998412e+06 51.872457

std 2.883286e+06 195.050858

min 1.160000e+02 0.000000

25% 2.512230e+06 5.000000

50% 4.995815e+06 16.000000

75% 7.496452e+06 51.000000

max 9.999861e+06 49854.000000

array(['gate_30', 'gate_40'], dtype=object)

Output Summary:

It appears that we have 90,189 rows populated over 5 columns, and no missing data! Perfect.

Our columns are userid, version, sum_gamerounds, retention_1, and retention_7. Only two columns contain

numeric variables, userid and sum_gamerounds. Userid reflects unique user ID’s, and sum_gamerounds reflects the number

of rounds played by each unique user. Version contains 2 groups, and will be the source of some of our AB groupings. As we

see from our EDA output, there are two levels, gate_30 and gate_40. Finally, our last two columns, retention_1 and

retention_7 are boolean values, True or False, indicating whether a player is still active after 1 or 7 days.

Like most “free” mobile games, there is an economic element for the craftsmen of the product to generate revenue. In this case,

there is a forced cool-down period after so many levels, which the player can remove by paying a fee. The version column

in our dataframe reflects versions with different gates preventing the player’s progress, after 30 levels or after 40, these

are recorded as gate_30 and gate_40.

These two versions allow us a fine entry point to AB testing.

Sample Size

Let’s first define the population sizes we’re dealing with to make sure we can proceed with a statistically sound comparison.

# Counting the number of players in each AB group.

A = df.version.groupby(df.version == "gate_30").count()

B = df.version.groupby(df.version == "gate_40").count()

print(A)

print(B)

Output:

` version False 45489 True 44700 Name: version, dtype: int64

version False 44700 True 45489 Name: version, dtype: int64 `

Of our 90,189 total records, approximately half are using version gate_30 (which we will call Group A) and the other half are using version gate_40 (which we will call version B).

This is great, we can proceed with the analysis.

How Much Do They Play?

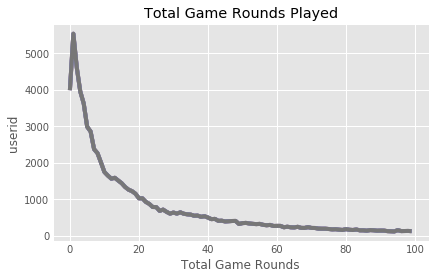

We want to see how many how long players typically stay with a product. One way to measure the metric in this case, is to examine how many rounds each user plays.

Since we’re using a Pandas DataFrame, we can take the following approach. We’ll use .groupby() to set each user’s experience

to a bin, and return a total count. We’ll then plot how many players are active within a set range, showing us the counts of

players within the 0-100 range of total rounds played.

# Counting the number of players for each number of gamerounds

plot_df = df.groupby("sum_gamerounds").count()

# Plotting the distribution of players that played 0 to 100 game rounds

ax = plot_df[:100].plot()

ax.set_xlabel("Total Game Rounds")

ax.set_ylabel("userid")

Conclusion:

It appears that the vast majority of users are playing less than 20 rounds in total, over the recording of this data.

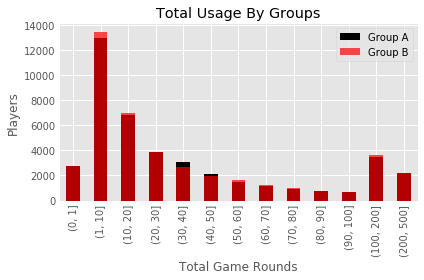

Let’s take the same approach to see if there is much of a difference in the number of games played in our AB versions allotted to each user.

Group Distributions: A vs B Total Plays

Set-Up

This time, we’ll need to massage the data a bit more. We’re also going to switch to an overlayed bar-plot of the distinct AB group distributions.

Since we’ve already identified that the drop off in users occurs in less than 20 sessions, let’s also change our bin distribution to get a more nuanced view of the low end and high end of user activities.

plt.style.use('ggplot')

# Counting the number of players for each number of gamerounds

Group_A = df[df.version == 'gate_30']

print(Group_A.head())

print(Group_B.head())

Group_B = df[df.version == 'gate_40']

bins = [0,1,10,20,30,40,50,60,70,80,90,100,200,500]

plot_GA = pd.DataFrame(Group_A.groupby(pd.cut(Group_A["sum_gamerounds"], bins=bins)).count())

plot_GB = pd.DataFrame(Group_B.groupby(pd.cut(Group_B["sum_gamerounds"], bins=bins)).count())

Plot It!

Remember, we’re going to overlay our graphs, so take particular notice of one approach that works

for our example, where we assign the second graph the parameter ax=ax to allow the overlay of the second distribution.

# Plotting the distribution of players that played 0 to 100 game rounds

ax = plot_GA[:50].plot(kind = 'bar', y="userid", color = "black", alpha = 1,

title = 'Total Usage By Groups')

plot_GB[:50].plot(kind = 'bar', y="userid", ax=ax, color = "red", alpha = 0.7 )

ax.set_xlabel("Total Game Rounds")

ax.set_ylabel("Players")

#plt.axvline(30, linestyle='dashed', linewidth=2)

#plt.axvline(40, linestyle='dashed', linewidth=2)

plt.legend(["Group A", "Group B"])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.grid(True)

There doesn’t seem to be a large difference between the two versions overall. However, there does seem to be some slight disparities around the 30-40 marks that may be related to the AB test at hand.

Please Come Back

Another metric we can use to guage the success of the product, is in the capture of returning users. If our revenue model is based on users, we don’t want them to give up on us early. Let’s look at how many players come back the day after installing the game.

# Calculate percent of returning users - next day

oneday = df.retention_1.sum()/df.retention_1.count()

print(str(oneday*100)+"%")

Output:

44.52% Return the day following an installation of the product.

Slightly less than half? Ok, just out of curiousity is there any fundamental difference in our two user populations from the start regardless of version impact? This time, let’s do as we did above, but this time group them by version group and see how the numbers pan out.

# Calculating 1-day retention for each AB-group

oneday = df.retention_1.groupby(df.version).sum()/df.retention_1.groupby(df.version).count()

print(oneday)

Output:

gate_30 44.818792

gate_40 44.228275

It looks like regardless of version, next day returns are essentially the same between our experimental groups.

But, there IS that 0.6% loss in return players randomized to the 40 round gate…could it be significant? Maybe this product will see millions of users and that extra 0.6% could translate into some paying customers and/or ad dollars.

It’s worth investigating.

We can use Bootstrapping to test our confidence. Bootstrapping is used in many disciplines, such as in molecular

biology to help the analysis of phylogenetics, to re-sample and replace data to and test our statistical confidence in our

results.

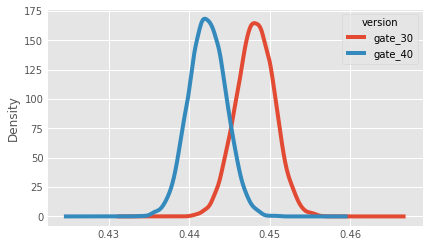

Bootstrapping Means - Sampling

# Creating an list with bootstrapped means for each AB-group

boot_1d = []

for i in range(500):

boot_mean = df.retention_1.sample(frac=1, replace=True).groupby(df.version).mean()

boot_1d.append(boot_mean)

# Transforming the list to a DataFrame

boot_1d = pd.DataFrame(boot_1d)

print(boot_1d)

# A Kernel Density Estimate plot of the bootstrap distributions

boot_1d.plot.kde()

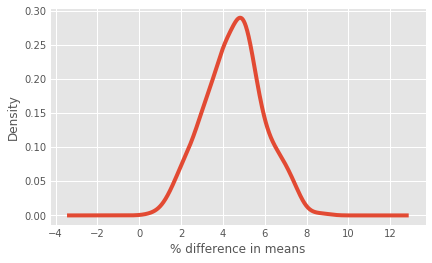

Calculating AB Group Percent Differences For A New Column, and Plotting

# Populate a new % Difference Column

boot_1d['difference'] = (boot_1d['gate_30'] - boot_1d['gate_40']) / boot_1d['gate_40'] * 100

# Plot the new Column

ax = boot_1d['difference'].plot.kde()

Calculating the probability that 1-day retention is greater when the gate is at level 30

prob = (boot_1d['diff'] > 0).sum() / len(boot_1d['diff'])

print(str(prob*100)+"%")

Output:

96.26%

Calculating 7-day retention for both AB-groups

sevenday = df.retention_7.sum()/df.retention_7.count()

print(sevenday)

Output:

0.186064819435

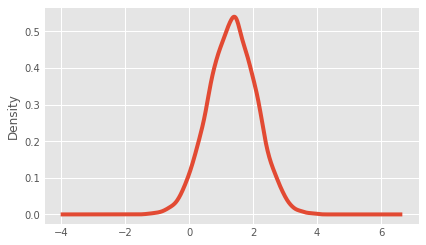

Creating a list with bootstrapped means for each AB-group

boot_7d = []

for i in range(500):

boot_mean = df.retention_7.sample(frac=1, replace=True).groupby(df.version).mean()

boot_7d.append(boot_mean)

# Transforming the list to a DataFrame

boot_7d = pd.DataFrame(boot_7d)

# Adding a column with the % difference between the two AB-groups

boot_7d['diff'] = (boot_7d['gate_30'] - boot_7d['gate_40']) / boot_7d['gate_40'] * 100

# Plotting the bootstrap % difference

ax = boot_7d['diff'].plot.kde()

ax.set_xlabel("% difference in means")

# Calculating the probability that 7-day retention is greater when the gate is at level 30

prob = (boot_7d['diff'] > 0).sum() / len(boot_7d['diff'])

# Pretty printing the probability

print(prob)